For a monoid \(M\), we can look at the group \(G\) that approximates \(M\) in the best way. If you have a presentation of \(M\) in terms of generators and relations, then \(G\) has the same presentation, but as a group rather than as a monoid. In other words, \(G\) is the group you get after formally adding inverses to the elements of \(M\). For example, if \(M\) is the monoid of natural numbers under addition, then \(G\) is the group of integers.

Usually, \(G\) is called the groupification of \(M\). Sometimes it is also called the Grothendieck group, but for some reason this name is only used when \(M\) is commutative.

Last week I found another name for the same construction, in Olivier Leroy’s thesis “Groupoïde fondamental et théorème de van Kampen en théorie des topos”. The construction there is more general: it associates a groupoid to a category, and Leroy calls this groupoid the fundamental groupoid of the category. Monoids are categories with one object, so taking Leroy’s terminology a bit further, the group associated to a monoid is its fundamental group.

It is an interesting name, because it suggests a relationship between this construction and covering spaces in topology, which is explained in Leroy’s thesis. I will give an example to show how this works.

The free monoid on two generators

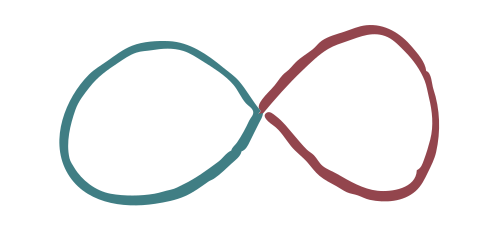

We will have a look at the free monoid \(M\) on two generators. So the elements are words using only the letters \(x\) and \(y\), and the multiplication is given by concatenation of words. We can draw \(M\) as follows:

What would be a good notion of covering space over \(M\)? The number of points should correspond to the degree of the covering map (the number of “sheets”). And each of these points should be “locally isomorphic to \(M\)”, in the sense that there should be precisely one blue arrow entering and one leaving, and similarly, there should be precisely one red arrow entering and one leaving.

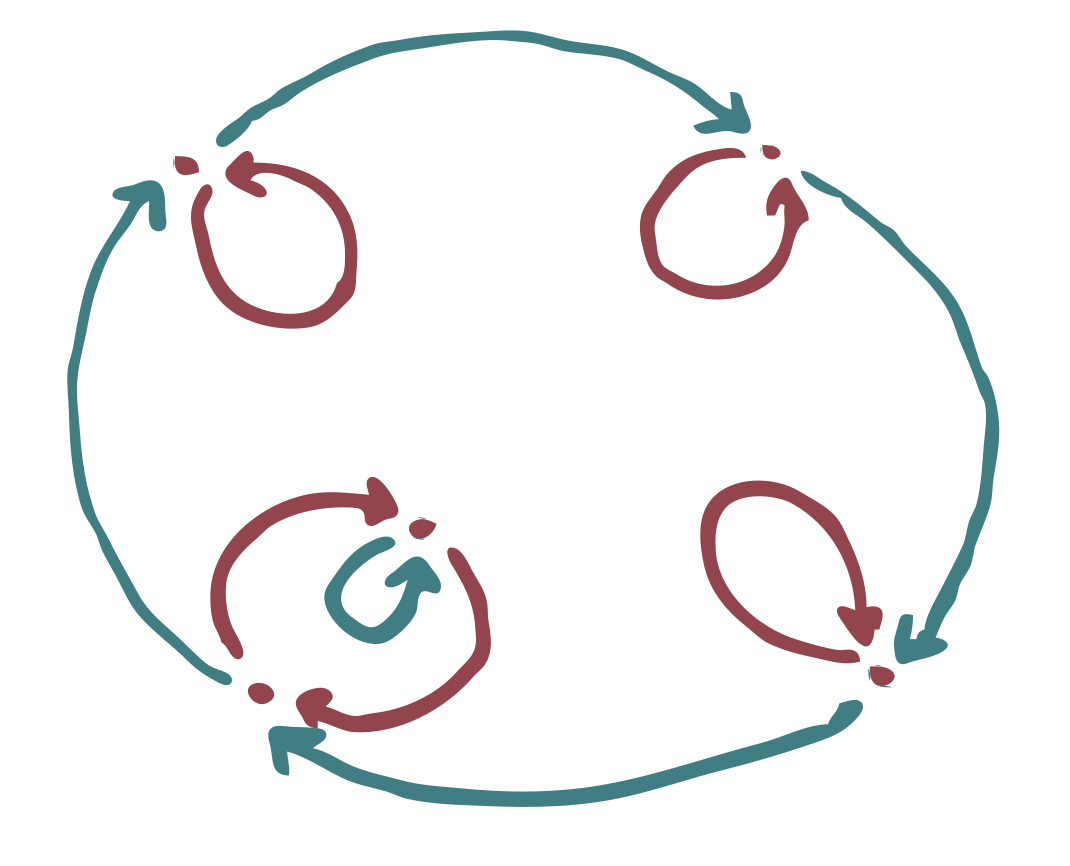

Here is an example of a covering space in this sense:

There is an action of the monoid \(M\) on the five points in the diagram. We can say that \(x\) acts by following the blue arrows on the left, and \(y\) acts by following the red arrows on the right. If we name the points \(v_1, \dots, v_5\) (from top to bottom), then we find for example that \(x\cdot v_1 = v_2\), \(x\cdot v_2 = v_3\), \(y \cdot v_1 = v_1\).

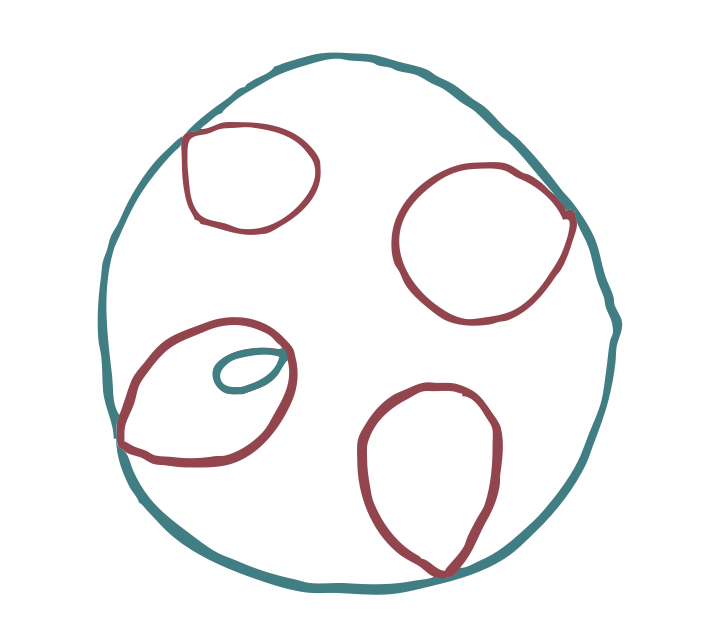

Every set with an \(M\)-action can be drawn as above, and the drawings that you get have the property that in each point there are exactly one blue arrow and one red arrow that leave this point. However, for an arbitrary set with \(M\)-action, we do not necessarily have exactly one blue arrow and one red arrow entering each point. Here is a counterexample:

What are the sets with \(M\)-action such that, if we draw them, there is precisely one blue arrow and one red arrow entering in each point? These are the sets for which \(M\) acts by permutations, and in turn these are precisely the ones such that the \(M\)-action extends to a \(G\)-action, where \(G\) is the free group on two generators, i.e. the groupification or fundamental group of \(M\).

So we see that covering spaces of \(M\) correspond to sets with a \(G\)-action. This is very similar to what happens in topology: for a connected, locally connected, semilocally connected topological space \(X\), we also have that covering spaces of \(X\) correspond to sets with an action of the fundamental group of \(X\).

The figure eight space

The topological space that most resembles the free monoid on two generators is probably the figure eight space (also known as two-petaled rose, lemniscate or infinity symbol).

Its fundamental group is the free group on two generators \(G\), so the monoid and the topological space even have the same fundamental group.

I claim that you can go from covering spaces of the monoid \(M\) almost instantly to covering spaces of the figure eight space. Let’s go back to the example:

We can rearrange the covering space to make it look more like a topological space.

To get the actual topological space, all we have to do is replace the arrows by line segments.

If we use \(X\) for the figure eight space, and \(Y\) for this covering space, then we also need to specify the covering map \(\pi : Y \to X\). You can do this by sending each line segment to the line segment of the same color in the base space.

However, it is not clear from this last drawing how to do this, because for each line segment there are two ways you can send it to the corresponding line segment in the base space (clockwise and counterclockwise, so to speak).

This means that in order to construct the covering map, you still need to remember the direction of the arrows.

Covering spaces of a category

The definition of covering space that we gave for the free monoid on two generators, is a special case of the notion of covering space for categories. The idea is that monoids are precisely the (small) categories that have one object. The arrows are the elements of the monoid.

Let’s see what the right notion of covering space is for a category.

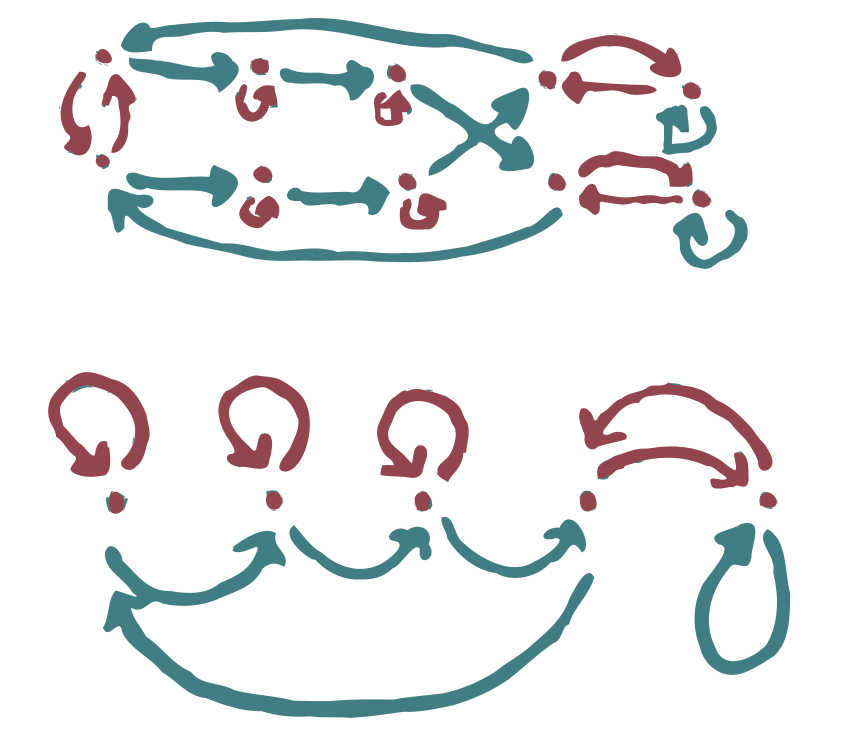

The first step is generalizing the monoid action. For a fixed category \(\mathcal{C}\), we can look at the functors \(\pi : \mathcal{D} \to \mathcal{C}\) with the property that for each arrow \(f: C \to C'\) in \(\mathcal{C}\) and each object \(D\) in \(\mathcal{D}\) with \(F(D)=C\), there is a unique “lifted arrow” \(\tilde{f} : D \to D'\) such that \(\pi(\tilde{f}) = f\). This is analogous to lifting paths in topology. It is also analogous to monoid actions: in some sense \(\mathcal{C}\) has a partially defined left action on the objects of \(\mathcal{D}\), via \(f \cdot D = D'\).

Functors \(\pi : \mathcal{D} \to \mathcal{C}\) like this are called discrete opfibrations. If you carefully compare the definitions, you see that they are the same thing as presheaves on the opposite category \(\mathcal{C}^\mathrm{op}\). (Technical comment: for this to work, we need that \(\pi^{-1}(C)\) is small enough to be a set, for every object \(C\) in \(\mathcal{C}\).)

When do discrete opfibrations (a.k.a. presheaves) qualify as covering spaces? In each object, we already have the right amount of arrows leaving, but we also need to specify how many arrows are entering. So we need that for each arrow \(f : C \to C'\) in \(\mathcal{C}\) and for each object \(D'\) in \(\mathcal{D}\) with \(\pi(D')=C'\), there is a unique \(\tilde{f}: D'' \to D'\) with \(\pi(\tilde{f})=f\).

In category theory jargon, in order to qualify as covering space, \(\pi\) should be a discrete fibration in addition to being a discrete opfibration.

Here is an example of a covering space (above) over some base category (below):

With the definition as above, the covering spaces on a category \(\mathcal{C}\) are the same thing as actions of the fundamental groupoid of \(\mathcal{C}\), i.e. the groupoid that you get by adding inverses to each arrow. If the category is connected, then the fundamental groupoid is equivalent to a group \(G\), and in this case covering spaces of \(\mathcal{C}\) correspond precisely to sets with a \(G\)-action.

Swept under the rug

As a category, the free monoid on two generators has one object and infinitely many arrows. Each arrow corresponds to an element of the free monoid, i.e. a word using the letters \(x\) and \(y\).

In my drawing of this free monoid, I only drew arrows for the generators, and ignored all other elements.

Why do we get away with this?

The reason is not easy to write out in detail, but it is more or less the following. For each directed graph \(\Gamma\) we can look at the category \(P(\Gamma)\) that has as objects the vertices of \(\Gamma\), and as morphisms \(v \to w\) the directed paths that start in \(v\) and end in \(w\).

Our definition of covering spaces works for directed graphs as well, and then you can show that a covering space \(\Gamma' \to \Gamma\) of a directed graph \(\Gamma\) extends in a unique way to a covering space \(P(\Gamma') \to P(\Gamma)\), and that all covering spaces of \(P(\Gamma)\) arise in this way.

We can then interpret the free monoid on two generators as the category \(P(\Gamma)\) where \(\Gamma\) is the directed graph with one vertex and two loops. So any covering space of this monoid can be described using a covering space of directed graphs \(\Gamma' \to \Gamma\).