The topos-theoretic formula in the previous blogpost can be very practical in concrete calculations. Here is a fun example featuring the Collatz conjecture. To be clear, the ideas in this blog post will not help in solving the Collatz conjecture. But the example might help to gain intuition about toposes.

The Collatz conjecture

Starting with a nonzero natural number \(n\), we follow this particular process: if \(n\) is even, we replace \(n\) with \(n/2\); if \(n\) is odd, we replace it with \(3n + 1\). The question is now: do we eventually reach \(1\)? Thanks to computer calculations, we now know at least that the answer is yes for all numbers with at most 20 digits. Once you reach \(1\), you are stuck in the cycle \(1,4,2,1,4,2,1,4,2,\dots\) The Collatz conjecture famously says that we eventually reach \(1\) for all starting values.

The Collatz conjecture is due to Lothar Collatz, who called it the \((3n+1)\)-conjecture. In a 1980 letter to Mays, Collatz mentions that he first thought about the problem in the early 1930’s. However, his first own article about the problem only appeared in the 1980’s, when his conjecture was already widely known. In this article, Collatz writes:

Since I could not solve the problem, I have not published the conjecture. I have mentioned the problem at many meetings and in many talks. In 1952, when I came to Hamburg, I explained the problem to my colleague Prof. Dr. Helmut Hasse. He was also interested in it. He has explained it in talks in other cities.

The paper is called “On the Motivation and Origin of the \((3n+1)\)-problem”, and appears as part of the book “The Ultimate Challenge: The \(3x+1\) Problem”, with Lagarias as editor. I believe that the writing style with rather short sentences is a result of the translation history of the paper: it was first translated to Chinese (probably from German), then back to German, and then to English. I enjoyed reading the paper (it is only 5 pages, including pictures).

Another quote:

I have experimented with many numbers. Before 1950 computers were not as well-developed as they are today. Therefore I could not try any large numbers.

Part of the appeal of the Collatz conjecture is that a counterexample would be extremely large (at least 21 digits), but this was not known yet in in the 1950’s when the problem became popular. With computers becoming more programmable and more powerful, the numbers up to 2 billion were checked by 1981 (now 40 years later, it took my laptop 1 hour to check the first 2 billion numbers, using Python code without any tricky optimizations).

The Collatz \(\mathbb{N}\)-set

The process described above is a discrete dynamical system, that we can model as a set \(X\) together with an action of the monoid \(\mathbb{N}\) of natural numbers under addition. First we take \(X\) to be the set of nonzero natural numbers. Now we define the function \(f\) as

\[f(n) = \begin{cases} n/2 & \text{if }n \text{ is even}; \\ 3n+1 & \text{if }n \text{ is odd.}\end{cases}\]and then we define \(n\cdot x\) to be the element that you get by starting with \(x \in X\) and then applying \(f\) precisely \(n\) times.

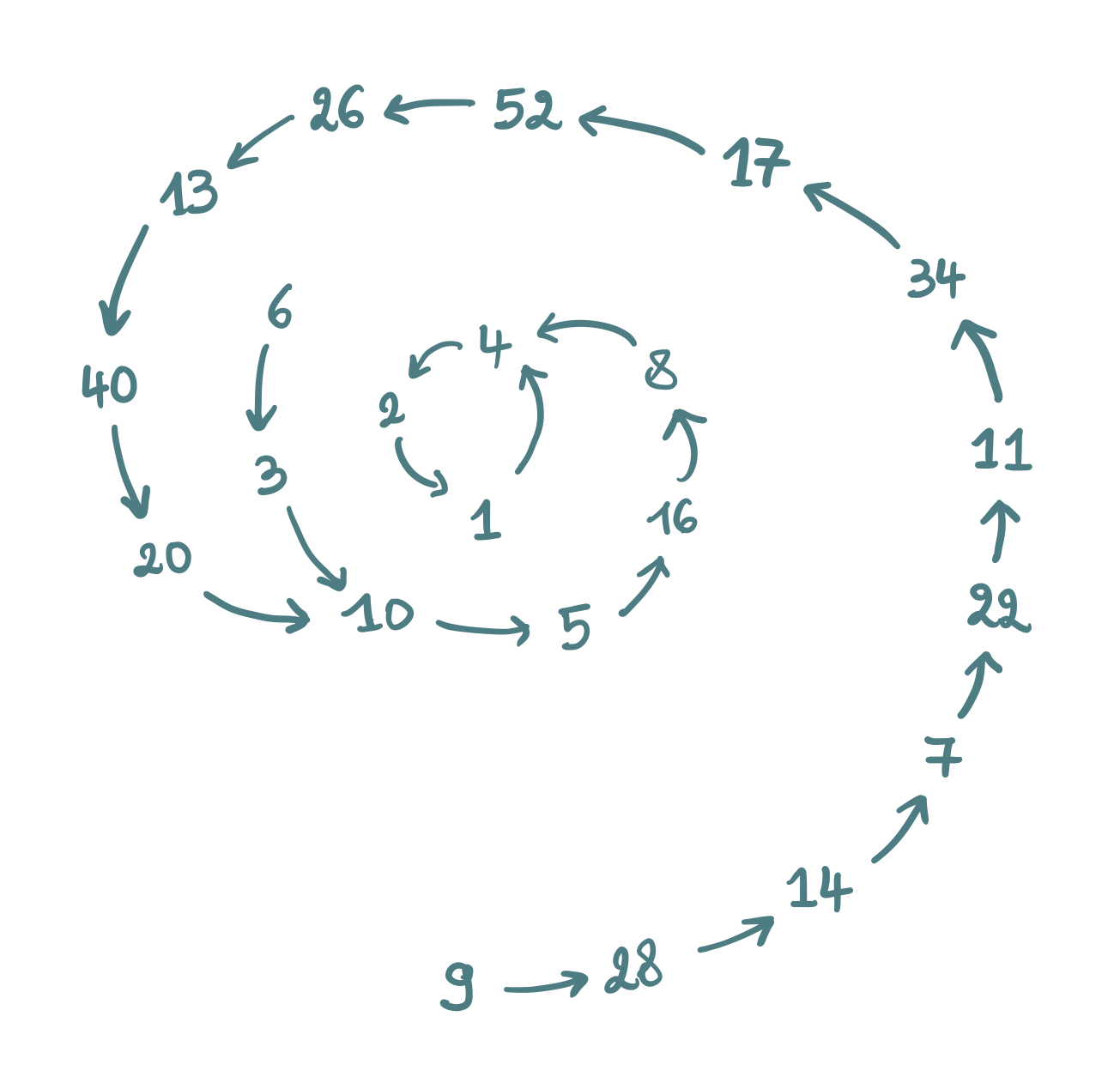

We can draw (part of) the Cayley graph of the \(\mathbb{N}\)-set \(X\) as:

This is the standard way of associating a graph to the function \(f\). The Collatz conjecture equivalently says that this Cayley graph is connected.

Collatz was originally looking for a simple arithmetic function \(f\) that has an interesting Cayley graph containing a loop. So his original problem was solved: we don’t know how many loops there are, but there is at least one.

The Collatz topos

If \(\mathbb{N}\) is the monoid of natural numbers under addition, then the category of \(\mathbb{N}\)-sets is a topos, namely the topos of presheaves \(\mathbf{PSh}(\mathbb{N})\) where we think of \(\mathbb{N}\) as a category with one object. We can also think of this as the topos of discrete dynamical systems.

For the \(\mathbb{N}\)-set \(X\) as above, we could then define the Collatz topos as the slice topos \(\mathbf{PSh}(\mathbb{N})/X\). Alternatively, this is the topos of presheaves \(\mathbf{PSh}(\int_\mathbb{N} X)\) where \(\int_\mathbb{N} X\) is the category with as objects the elements of \(X\), and as morphisms \(x \to y\) the elements \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(x = y\cdot n\).

In this way, we can represent this dynamical system in a geometric way. This is very similar to the Cayley graph construction above. Similar to how the Cayley graph is a disjoint union of connected components, the Collatz topos is also a disjoint union of connected components, and the Collatz conjecture holds precisely if the topos is connected.

Isn’t this a bit pointless?

Yes, building this “Collatz topos” is pointless, if your goal is proving the Collatz conjecture. Topos theory has a history of providing useful insights in mathematical problems, but in this case it is unlikely (maybe even impossible) that the construction of this Collatz topos will be of any help. On the other hand, when learning about toposes, this Collatz topos could be a fun example.

Unrelatedly, there is the concept of point of a topos. In this mathematical sense, the Collatz topos is the complete opposite of pointless: it has enough points.

Points are geometric morphisms from \(\mathbf{Sets}\) to our topos. To compute these, we can look at the formula

\[\mathbf{Geom}(\mathcal{F},\mathcal{E}/X) ~\simeq~ \int^{f \in \mathbf{Geom}(\mathcal{F},\mathcal{E})} \mathrm{Hom}_{\mathcal{F}}(1,f^*(X)).\]In our case, we get

\[\mathbf{Geom}(\mathbf{Sets},\mathbf{PSh}(\mathbb{N})/X) ~\simeq~ \int^{f \in \mathbf{Geom}(\mathbf{Sets},\mathbf{PSh}(\mathbb{N}))} \mathrm{Hom}_{\mathbf{Sets}}(1,f^*(X)) ~\simeq~ \int^{f \in \mathbf{Geom}(\mathbf{Sets},\mathbf{PSh}(\mathbb{N}))} f^*(X).\]If the notation doesn’t make any sense, you can have a look at the part about the Yoneda notation in the previous post.

All that remains now is to determine \(f^*(X)\) for every \(f\) in \(\mathbf{Geom}(\mathbf{Sets},\mathbf{PSh}(\mathbb{N}))\). Here some work needs to be done, and I’ll just mention the end result of the calculations.

Up to isomorphism, the points of the Collatz topos are given as follows:

- there is a point for each natural number \(n\), corresponding to a “state” in the Collatz sequence;

- there is a “point at infinity” for every connected component in the Cayley graph.

The points corresponding to a natural number do not have nontrivial automorphisms. For the points corresponding to connected components, it depends on whether or not the connected component ends in a loop. If it does, then the automorphism group is isomorphic to the group of integers; if not, then the automorphism group is trivial.